What Our Soil is Telling Us

-

by Anoop Singh

- 4

Eco-acoustic studies at Flinders University indicate that healthier soils have more complex soundscapes, pointing to a novel tool for environmental restoration.

Healthy soils produce a cacophony of sounds in many forms barely audible to human ears – a bit like a concert of bubble pops and clicks.

In a new study published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, ecologists from Flinders University have made special recordings of this chaotic mixture of soundscapes. Their research shows these soil acoustics can be a measure of the diversity of tiny living animals in the soil, which create sounds as they move and interact with their environment.

With 75% of the world’s soils degraded, the future of the teeming community of living species that live underground faces a dire future without restoration, says microbial ecologist Dr. Jake Robinson, from the Frontiers of Restoration Ecology Lab in the College of Science and Engineering at Flinders University.

This new field of research aims to investigate the vast, teeming hidden ecosystems where almost 60% of the Earth’s species live, he says.

Advancements in Eco-Acoustics

“Restoring and monitoring soil biodiversity has never been more important.

“Although still in its early stages, ‘eco-acoustics’ is emerging as a promising tool to detect and monitor soil biodiversity and has now been used in Australian bushland and other ecosystems in the UK.

“The acoustic complexity and diversity are significantly higher in revegetated and remnant plots than in cleared plots, both in-situ and in sound attenuation chambers.

“The acoustic complexity and diversity are also significantly associated with soil invertebrate abundance and richness.”

The study, including Flinders University expert Associate Professor Martin Breed and Professor Xin Sun from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, compared results from acoustic monitoring of remnant vegetation to degraded plots and land that was revegetated 15 years ago.

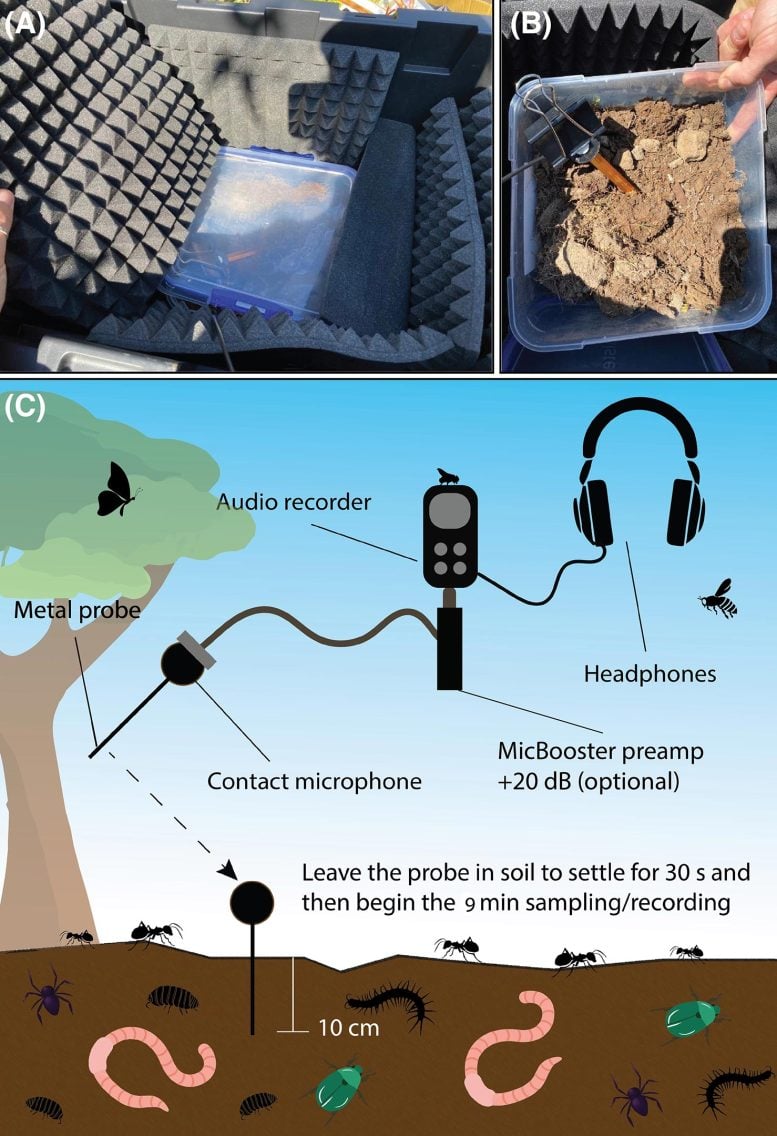

The passive acoustic monitoring used various tools and indices to measure soil biodiversity over five days in the Mount Bold region in the Adelaide Hills in South Australia. A below-ground sampling device and sound attenuation chamber were used to record soil invertebrate communities, which were also manually counted.

“It’s clear acoustic complexity and diversity of our samples are associated with soil invertebrate abundance – from earthworms, beetles to ants and spiders – and it seems to be a clear reflection of soil health,” says Dr. Robinson.

“All living organisms produce sounds, and our preliminary results suggest different soil organisms make different sound profiles depending on their activity, shape, appendages, and size.

“This technology holds promise in addressing the global need for more effective soil biodiversity monitoring methods to protect our planet’s most diverse ecosystems.”

Reference: “Sounds of the underground reflect soil biodiversity dynamics across a grassy woodland restoration chronosequence” by Jake M. Robinson, Alex Taylor, Nicole Fickling, Xin Sun and Martin F. Breed, 15 August 2024, Journal of Applied Ecology.

DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.14738

Australian ecologists from Flinders University use eco-acoustics to study soil biodiversity, discovering that soundscapes in soils vary with the presence and activity of various invertebrates. Revegetated areas show greater acoustic diversity compared to degraded soils, suggesting a new approach to monitoring soil health and supporting restoration efforts. Eco-acoustic studies at Flinders University indicate that healthier…

Australian ecologists from Flinders University use eco-acoustics to study soil biodiversity, discovering that soundscapes in soils vary with the presence and activity of various invertebrates. Revegetated areas show greater acoustic diversity compared to degraded soils, suggesting a new approach to monitoring soil health and supporting restoration efforts. Eco-acoustic studies at Flinders University indicate that healthier…