Yes, Rock Climbing Is bad For Your Joints Climbing

-

by Anoop Singh

- 22

“], “filter”: “nextExceptions”: “img, figure, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, figure, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button” }”>

You are three days into the last week of your climbing trip, repeatedly trying a fingery project or that tweaky shoulder move. When an old swelling in the finger joints or aching in the shoulder returns, you shrug it off, thinking, I just need a rest day. True, but is that the only solution?

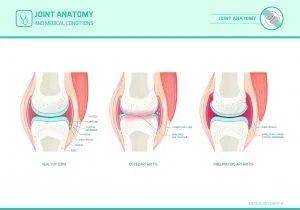

Our joints take a beating with climbing, which can wear away the precious two to four millimeters of cartilage that act as a cushion between our bones. Although a certain amount of joint stress is key to maintaining cartilage health, too much too often—through impact, compressive, or shearing forces—can lead to degenerative changes. Studies such as one on inflammation and osteoarthritis published in Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease (2013) tell us that even if your joints are currently in decent health, chronic inflammation is a major driver of degenerative changes down the road. So pay attention to recurring bouts of swollen fingers (aka synovitis), a common ailment among climbers! Even though science is hard at work for solutions to regenerate cartilage, our best defense is prevention, or changing the things we can.

Here are top tips for maintaining healthy joints:

Section divider

I. Manage Your Form

Study how you move. The way we move influences the stress on our joints and tissues.

So-called “overuse” can be caused not just by overdoing it in climbing, but from repetitive poor form. For example, habitually climbing with our elbows flared out can place excessive strain on the elbow and shoulder joints. Weakness in certain muscles, inability to control movement (such as decelerating or downward moves), or lack of mobility in one area may cause us to compensate elsewhere, creating excessive stress to joints and tissues at the end of the kinetic chain. An example could be that a lack of hip mobility, whether passive or active, forces you to move more from the lower back, stressing the joints and discs there.

Elbows

When you pull down, keep your elbows close to the wall/rock and in line with your trunk—minimize chicken-winging. Of course, most of us chicken-wing a bit when we get pumped or struggle. However, we can minimize how often it occurs. Think of overuse as being like a bank account. We can only take so many withdrawals until nothing is left. On slopers, try to protect your wrists by keeping them straight versus bent. Try to keep your hips close to the wall, which can also help direct the line of pull on the wrist and fingers. Imagine the placement of your wrists and fingers on a sloper if your butt is sticking out away from the wall. The sloper is harder to hold, since a sloper is often easier to stay on when you pull straight down on it. A poor body position may result in using a different grip position and/or gripping harder to stay on, causing avoidable stress on muscles and tendons.

Wrists and Fingers

From a training standpoint, having better strength and endurance in our wrists and fingers may help prevent abnormal movements, such as chicken winging, especially as we become pumped or try crux moves. Becoming stronger on open-handed grips can decrease our reliance on crimping, saving our finger joints from the compressive and shear forces that arise in using crimps—especially when a foot pops and we stress that position unexpectedly.

We can improve our finger strength with hangboarding using open-handed and half-crimp positions on edges. Hanging on slopers can help develop strength in the wrist flexors. Performing wrist curls is a fine, isolated way to gain strength in the wrist flexors, especially for novice climbers who do not have a broad foundation in usage. However, I would recommend that intermediate and seasoned climbers focus more on strengthening in positions specific to the demands of the sport (i.e., on hangboards or slopers).

Osteoarthritis is a result of wear and tear and repeated bouts of inflammation that can be caused by less-than-ideal climbing techniques and injuries. The left joint shows a healthy cushion of cartilage between the bones, while the right joint has severe cartilage detoriation resulting in bone-on-bone contact.

Train for Quality Rather than Quantity

Quality is always better than quantity. Finish your training or climbing session with enough energy to maintain some semblance of good form. Increased load to a joint or tissue plus abnormal movement create the perfect storm for injury. A simple example would be trying weighted pullups. Let’s say you’ve heard that those are good for increasing pulling strength. You are unaware that you already have poor form with body-weight pullups, and are excessively stressing the shoulders or elbows. Adding additional weight not only further worsens this poor form but creates more load with an already stressful movement. It could cause a sudden or, with repetition, gradual injury such as a shoulder subluxation.

Video Yourself

Take some video of yourself climbing. The “why” of the way you move may need further investigation. Is an error such as chicken winging or poor body positioning a learned strategy (a bad habit) or caused by deficits in strength, control or mobility? Working with a seasoned climbing coach, sports-performance coach or physical therapist (hint, hint) can help.

Section divider

II. Increase Tissue Mobility

Myofascial restrictions, created by adhesions in the web of connective tissue (fascia) that encases underlying muscle, bone, blood vessels and nerves, can contribute to joint pain in the fingers and hands. Addressing these mobility restrictions from the neck to the hand is important to relieve tension throughout our upper extremities and reduce stress on neighboring tissues such as tendons.

Massage, Active Release and Trigger Point

Deep-tissue massage, active release and trigger-point release/dry needling are all good options. How often to perform them depends on the chronicity of the issue. If the issue is a recent occurrence (e.g. it happened right after a training session) and addressed early, one or two treatment sessions may suffice. More chronic cases may take more daily treatment or some time each session for several days. Once the spot is no longer tender and feels supple instead of hard, you can decrease the frequency, but reassess weekly, especially after consecutive hard days of climbing/training. If you want to have deep-tissue massage, I recommend getting it two days before competing or trying to send a project, as you might be sore the next day. Trigger-point release can be done any time, even during competition. Although you may experience some soreness, the benefits should outweigh the negatives.

Section divider

III. Leverage Nutrition

There is growing evidence, as per a study presented in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2017), that consumption of collagen-rich gelatin with the amino acids glycine and proline and with vitamin C, combined with light exercise, can improve tendon health through a significant increase in collagen synthesis. There are products on the market, but you can also get these amino acids through natural sources such as pork, fish and chicken, to name a few. To date, I am unaware of vegan sources of supplementation.

Exercise is important for delivering the nutrients to the injury site. Lightly stressing the tendons helps them to absorb nutrients and promotes collagen synthesis naturally.

Based on current literature, it is recommended to ingest collagen-rich gelatin with vitamin C one hour before some light exercise for five or six minutes. For more specifics and customized plans, I recommend consulting with a sports nutritionist familiar with the subject. Although the evidence for use of this combination in rehab is limited, research has been promising.

Section divider

IV. Nuanced Hydration

Hydrate! Water is vital for joint health. Water is the most abundant ingredient in our cartilage, making up 65 to 80 percent of its total weight. In addition to lubricating our joints, water helps us withstand significant loads and nourishes the cells that develop, maintain and repair our cartilage. The general recommendation is to drink 30 to 50 ounces per day; athletes need far more. Drink 16 ounces two hours before activity, and eight ounces every 15 to 20 minutes during activity.

Finally and again, your top priority should be to become aware of how you move. Seek to find out why you move in those less-than-ideal ways. Assess your tissue mobility weekly, and hydrate enough—it’s the simplest thing of all, but key.

“], “filter”: “nextExceptions”: “img, figure, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, figure, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button” }”> Table of Contents Manage Your Form Increase Tissue Mobility Leverage Nutrition Nuanced Hydration You are three days into the last week of your climbing trip, repeatedly trying a fingery project or that tweaky shoulder move. When an old swelling in the…

“], “filter”: “nextExceptions”: “img, figure, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, figure, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button” }”> Table of Contents Manage Your Form Increase Tissue Mobility Leverage Nutrition Nuanced Hydration You are three days into the last week of your climbing trip, repeatedly trying a fingery project or that tweaky shoulder move. When an old swelling in the…